- Home

- health

- Balancing Innovation and Safety: The Ethical Dilemma of New Surgical Techniques

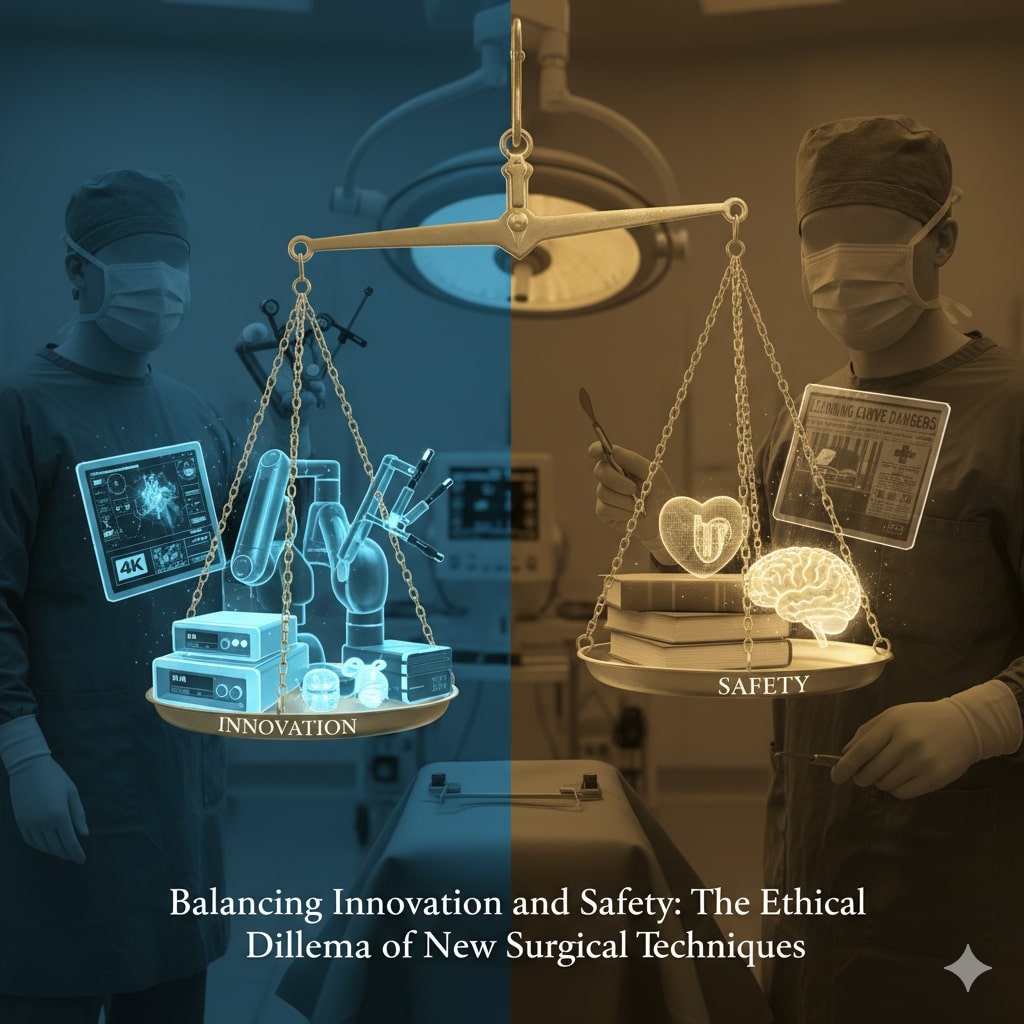

Balancing Innovation and Safety: The Ethical Dilemma of New Surgical Techniques

Source from PubMed Central

health

9/21/2025Shathamanyu

In the fast-evolving world of surgical innovation, a critical question persists: how can we advance new surgical techniques

without compromising patient safety?

Since the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the late 1980s, the field of surgery has seen dramatic shifts—from

standard open procedures to high-tech laparoscopic and robotic-assisted operations. Yet, as history and recent studies show, these

advancements sometimes come with unintended consequences.

In 1992, journalist Lawrence K. Altman warned in The New York Times about the dangers of the “learning curve” in new surgical

procedures. His concern was clear: in the race to adopt new techniques, patients might pay the ultimate price.

Three decades later, his concerns remain relevant.

New technologies such as the Da Vinci robotic system and 4K laparoscopic devices have transformed complex procedures like liver

resections and pancreatic surgeries. However, these innovations often lack comprehensive long-term outcome data. A stark reminder

came in 2018 when MD Anderson Hospital published two studies in The New England Journal of Medicine. Both revealed significantly

higher recurrence and mortality rates in minimally invasive surgeries for early-stage uterine and cervical cancers compared to

traditional open surgeries. One study had to be halted prematurely due to the increased risks.

These findings triggered a change in treatment protocols and highlighted the ethical obligation of surgeons to choose the safest

option—not merely the most advanced.

Experts argue that rigorous traditional surgical training must precede the adoption of newer technologies. Surgeons trained in

open procedures possess a deeper understanding of anatomy and surgical flow, allowing them to transition more safely into

minimally invasive approaches. Many professional bodies now require specific training benchmarks before permitting surgeons to

operate with laparoscopic or robotic tools.

Still, pressure from industry, institutions, and even personal ambition can blur ethical lines. Surgeons, often eager to master

cutting-edge procedures, may unintentionally place patients at risk during their learning phase. This risk is especially high in

low-volume hospitals, where complex surgeries are infrequent.

In developed countries, robotic and laparoscopic surgeries dominate high-tech surgical centers. Yet, in developing regions,

traditional methods remain the backbone of care. This global imbalance emphasizes the importance of integrating high-tech

innovations into solid foundational surgical training, rather than replacing it.

Artificial intelligence and autonomous surgical robots are already on the horizon. However, as one fatal case in the UK

demonstrated, deploying technology without sufficient expertise or transparency can lead to tragic outcomes. Patients deserve full

disclosure—especially when they are part of a surgeon’s first attempt at a novel technique.

Ultimately, the goal is not to halt innovation but to guide it responsibly. Surgical advancements must enhance long-term patient

outcomes, not just satisfy the allure of modernity. In the balance between progress and safety, ethical judgment must always lead

the scalpel.

Recent news

Related News